So, you’ve invented something you believe will change the world and earn you a small (or large!) fortune. Congratulations!

Now what…

If you’re reading this article, you’re probably familiar with the concept of patents and how they can protect your idea. I’m sure many of you have seen patents mentioned in the news and read about the huge battles that take place between corporate giants such as Apple, Qualcomm, and Samsung. In many cases, the settlement sums involved can be enormous!

But how can you get one? and, importantly, how do you use them to your benefit?

To answer these questions, we need a fundamental understanding of what a patent is and the rights it gives to the owner…

Patent Definition

In its broadest sense, a patent is a monopoly right granted to the owner of an invention by a government or intergovernmental organisation for a limited period (typically up to a maximum of 20 years).

The granted patent gives the owner the right to prevent any unauthorised third party from working the invention in the territory in which the patent is granted and in force. For example, a Hong Kong patent gives the owner the right to prevent others from working the invention in Hong Kong.

Two questions may arise from this passage. How do you define ‘invention’? and what is meant by ‘working’?

Meaning of ‘Invention’

Patent laws do not give a precise definition of what an invention is. However, they do provide guidance as to what a patentable invention is not and the criteria that must be met to be granted a patent for an invention.

To help our understanding, let’s start with an example.

Keeping it simple, let’s transport ourselves back a few thousand years and imagine we’ve invented the chair. I’ve used the word ‘chair’ so that you, the reader, immediately know what I’m talking about. Of course, when you read the word chair, you have a very good understanding of what it is and how it works. This is because, in the present day, chairs are one of the most common products on the planet!

But in this example, we must imagine no chair has ever existed before. Consequently, in 20,000 BC we don’t even have a word for it yet! So how are we going to describe our invention to Barney Rubble next door?

There are a few obvious ways in which we might begin to explain the invention. In this example, drawings would clearly be extremely useful. It might be that we have only one chair design or that we have multiple chair designs. Either way, we’ll draw one or more examples of what we believe a chair to be.

Next, we’ll prepare a written description (we’ve invented writing by this point…) of our chair with reference to the drawings. Our description will include all the features that we believe are required to make our chair work. To aid understanding, we could include reference numerals next to each feature in our description and include corresponding reference numerals in our drawings. This will help Barnie to quickly locate the corresponding features in the drawings and gain a good understanding of our invention.

Now, since a patent gives the owner the right to prevent others from working our invention, we need a very clear definition of what our invention is so that third parties know what they are not allowed to do. Clearly, without a precise definition, it would be very difficult for Barney to know what our patent excludes him from doing without our authorisation.

Therefore, we must prepare so-called ‘claims’ which define, in precise terms, our invention and the essential features required to work our invention. For example, we might state that our chair requires at least one leg and a seat supported by at least one leg so that when the chair is placed on supporting surface, the seat is supported by the leg and spaced apart from the supporting surface. With this definition, Barnie knows that he cannot make his own chair with at least one leg and a seat that perform the stated functions.

Our description, claims, and drawings make up our patent document which is used by the patent granting authorities to assess whether our invention satisfies the criteria for being granted a patent.

Basic Patentability Criteria

Obviously, a patent should not be granted for something that has already been done before. Fast forward 20,000 years to present day and you can imagine the carnage if we were able to obtain a patent for a chair and start suing every chair manufacturer, distributor, and retailer on the planet!

Therefore, patent laws have evolved to only grant patents for inventions that meet minimum basic criteria.

Novelty

The first of these is that the invention (as defined by the claims) must be new. Here, ‘new’ means that the same invention (that is a product, process, or method) has never been disclosed to the public before. In assessing whether an invention is new, a granting authority or ‘patent office’ can search for earlier material that discloses the same invention. In most jurisdictions, this earlier material includes anything that has ever been published in all human history. We call this earlier material ‘prior art.’

Importantly, prior art can include anything the inventor has disclosed to the public before an application for the invention has been filed. Therefore, it’s very important for inventors to keep their inventions confidential until a patent application has been filed.

This novelty criterion should be (but often isn’t) a straightforward, black and white concept. Either something exists with the same features as those in the claims of the patent application or it doesn’t. Simple! I wish…

Inventive Step

The second basic criterion is that the invention must involve an ‘inventive step’. Often, an invention will meet the novelty criterion and exhibit one or more differences from the prior art. But then the question arises, how different does your invention have to be to be granted a patent? Clearly, we should not be granted a patent for a furry, rainbow coloured chair with polka dot legs just because no-one ever thought of this combination before (I’m assuming this is new, but it probably isn’t!!). This is where inventive step comes into play.

An invention is determined to involve an inventive step if the differences that give it novelty are not obvious to a ‘person skilled in the art’. In this context, a person skilled in the art is a hypothetical individual or team of individuals that specialise in the field of the invention and that has knowledge of all prior art. This person skilled in the art is not very inventive but can combine the teachings of different prior art documents to try to overcome the problem addressed by the invention. You might think of this person as a basic artificial intelligence.

As you’ll appreciate, this criterion is more subjective than the novelty criterion, and is often a judgement call made by an examiner at the relevant patent office.

Industrial Applicability

The third fundamental criterion for a patentable invention is that it is capable industrial application i.e. the product or process can be made or used in some kind of industry.

Meaning of ‘Working’ the Invention

Hopefully, you now have a basic understanding of what a patent is, how we define an invention, and how the invention is assessed to determine whether a patent can be granted.

Assuming we overcome all these hurdles and obtain our patent, what can we prevent others from doing?

As we alluded to earlier with the story of Barney and the chair, one of the acts our patent allows us to prevent is manufacturing the patented product. What other acts can we prevent?

In relation to a patented product, the patent can generally be used to prevent an unauthorised third party from putting the product on the market, using or importing the product, or stocking the product in the territory in which the patent is in force.

In relation to a patented process, the patent can generally be used to prevent an unauthorised third party from using the process or offering the process for use in the territory in which the patent is in force. The patent may also be used to prevent the sale, use, importation, or stocking of a product obtained directly by the patented process.

As you’ll appreciate the patent provides quite ranging power and can make it very difficult for a competitor to enter a market in which you have one or more patents.

The Patent Specification

So, we know how great patents can be and how they can give your business a competitive edge, but how do you obtain one?

We briefly touched on this in our chair invention example but the first step in the process is to prepare a patent specification that describes your invention in detail and that includes one or more drawings to assist with understanding. The patent specification is usually comprised of four key sections, namely the background, the statements of invention, the description, and the claims.

Background

The background section typically discusses the field of the invention, the existing prior art (if any), and one or more problems associated with the prior art e.g. too slow, break too easily, are too inefficient etc. By discussing the problems with the prior art, the solution proposed by the invention can be made to sound like a big leap forward that no-one would ever think of i.e. inventive!

Statements of Invention

The statements of invention generally list out the key features of the invention. Many patent specifications will include as many different possibilities or alternative features that will work as part of the overall inventive concept. One common approach is to repeat the claims in this section and discuss the various advantages associated with the recited features.

Detailed Description

The description should include a very detailed explanation of how the invention works and is put together and refer to any helpful drawings. It’s appropriate to include in this section specific components and how they are arranged and configured. It’s useful to write this section as if you were creating a blueprint that would enable a third party to reproduce your invention.

Claims

Finally, the hardest part… the claims. As mentioned above, the claims define the scope of protection and, hence, indicate to third parties the boundaries of your territory. They should include the minimum number of essential features necessary for your invention to work but should also define something that is new and arguably inventive.

If you include too many non-essential features in your claims, your scope or boundary of protection will be too small, and your patent may be easy to ‘engineer around’ i.e. allow a third party to leave out one or more features without infringing the patent.

If you include too few features in your claims, your scope of protection may be too broad such that the definition covers one or more existing solutions. In this scenario, your invention as defined by the claims will not be new or may not differ from the prior art in an inventive way.

Claim drafting is a balancing act and will usually require a great deal of thought and stress testing. When stress testing a claim, you need to consider which features you might safely omit or whether a listed feature could be replaced by an alternative feature without drastically affecting the operation of the invention.

If you find that one or more features are not absolutely essential to the invention or that your definition does not cover an alternative solution that is similar but not the same as your prototype or specific example, you may need to amend your claims until you find a combination of features that provides relatively broad protection, makes it difficult for third parties to engineer around, and distinguishes your invention from known solutions… it’s not easy!

Pre-filing Search (Optional)

In preparing a patent specification, it’s often a useful exercise to conduct a patent search. A patent search involves a keyword-based search that seeks to locate relevant prior art. Often this involves using a patent search engine to enter a combination of words that you believe are most likely to relate to your invention. For example, in the case of our chair invention you might enter ‘leg’, ‘seat’, ‘back’, and ‘support’ into a popular search database such as Espacenet and review the results.

Patent searching can be a dark art and conducting a comprehensive search is a topic for a whole other article!

Whilst a pre-filing patent search is optional, the results are often useful in deciding what features of your invention are new and, hence, which aspects to focus on when drafting the claims and the description.

Once the patent specification has been prepared, we need to file the initial patent application or ‘first filing’…

The First Filing

To initiate your application, you need to submit your patent specification to a patent office together with a request for grant of a patent and, if required on filing, payment of official fees.

Generally, your first patent application will be submitted to the patent office of the country in which the invention was reduced to practice (although it can get complicated with certain nationalities and with inventions having multiple inventors in multiple different jurisdictions!).

This first filing is very important because its filing date is used to determine what constitutes prior art in relation to your invention.

In the strictest jurisdictions, the prior art will comprise everything made available to the public before the date of filing of your patent application. Therefore, as stated above, it’s essential to file your patent application before you disclose any details to the public and to do so as early as possible to minimise the amount of prior art that can be used to challenge the patentability of your invention i.e. whether it’s new and/or inventive.

At this stage, you might be wondering what you can do about filing patent applications overseas. Whilst your home country might be important to your commercial activities, there may be other markets that are equally, if not more, important, or potentially important, to your business.

This is where the ‘priority date’ and the ‘priority window’ come into play.

Filing Overseas

Your first filed patent application for your invention establishes a ‘priority date’ for your invention and initiates a 12-month priority window in which to file corresponding patent applications overseas. Provided you file a corresponding patent application overseas within this 12-month window, you will have the right to claim priority to your first filed patent application.

With a valid priority claim, provided certain criteria are met, your overseas patent applications will be treated as if they were filed on the same day as your first filed patent application even though they were filed 12-months later.

For example, if you file a Hong Kong short term patent application on 1 October 2018 and a corresponding European patent application on 1 October 2019 with a claim to priority to your Hong Kong short term patent application, your corresponding European patent application will be treated, for the purposes of assessing patentability, as if it was filed on 1 October 2018. Thus, a European examiner can only rely on prior art that was disclosed to the public or, in the case of a published patent application, filed before 1 October 2018, rather than 1 October 2019, in assessing whether your invention is new and inventive.

You will appreciate that this 12-month priority window can be a very useful way to delay relatively costly overseas patent filings. However, what if 12 months is not enough and you need more time to raise the capital to fund your patent applications? This is where the international patent application, commonly referred to as a PCT, can be used.

International Patent Application Under the PCT

As the name suggests, the Patent Co-operation Treaty, or PCT, is an international patent law treaty through which member states co-operate in relation to the filing of patent applications and reciprocating certain rights. At the time of writing, there are 152 member countries/organisations of the PCT. An up to date list is available here. As you’ll see, two notable non-members are Argentina and Taiwan which means the PCT cannot be used to delay filing your patent application in either of these countries.

With a few exceptions, an international patent application filed under the PCT may be entered into (filed in) one or more member states within 30 or 31 months (depending on member state preference) from the earliest priority date. The time limit for each member state or organisation are available here. You should only consider the ‘Chapter I’ column at this stage so as not to overcomplicate matters.

Usefully, just as with an overseas patent filing, an international patent application can claim priority to a first filed patent application. Therefore, if an international patent application is filed at the end of the 12-month priority window and claims priority to a first filed patent application, it will give the applicant a further 18 months to decide the other countries in which to proceed (provided they are PCT member states).

An international patent application can therefore be useful if an applicant does not have the funds in place to proceed with multiple overseas filings at the end of the 12-month priority window and/or if the applicant wants to delay the decision as to the countries in which to pursue patent protection.

For example, it might be that an applicant is seeking investment and does not want to commit to specific countries until the investors are on board. This can help to avoid a situation in which an applicant commits to US, China, and Europe at the 12-month stage, only to find that its subsequent investors were also interested in Japanese and Australian markets.

The Examination

Regardless of the various routes taken by the applicant, when a patent application is filed with a patent office, it must undergo an examination to check whether a patent can be granted. The type and extent of the examination varies by jurisdiction.

In some jurisdictions, the examination may involve a simple formality check with no assessment of patentability.

In most major jurisdictions, though, such as China, Europe, US, and Japan, the process involves a far more thorough ‘substantive examination’ in which the patent office examiner will assess the novelty and inventive step of the claimed invention.

It’s important to note that this examination process can take many years!

As part of the substantive examination procedure, the examiner will conduct a patent search to try to find relevant prior art documents or ‘citations.’ Any citations revealed by the examiner’s search will be communicated to the applicant, usually with an indication as to how relevant each document is from a patentability perspective.

Based on the search results, the examiner will issue a first examination report with details of his/her objections, if any, and indicate a period in which to respond or act. This report may indicate none of the claims define an invention which is new, or that some of the claims define an invention which is new but not inventive, or that all or some of the claims are new and inventive.

The details of the first examination report will determine how the applicant might proceed.

If the report is particularly unfavourable and raises extensive objections to the application, the applicant may decide it’s no longer worth pursuing and allow the application to become abandoned.

If objections are raised but the applicant disagrees, the applicant may decide to present arguments to the examiner as to why the invention defined by one or more claims is new and inventive over any cited prior art. As part of this response, the applicant may introduce one or more additional key features into a claim to help distinguish or further distinguish the claimed invention from the prior art.

A response can persuade the examiner to change his/her mind but, if not, a further examination report with the same or new objections may be issued. At this point, it’s a matter of rinse, recycle, repeat.

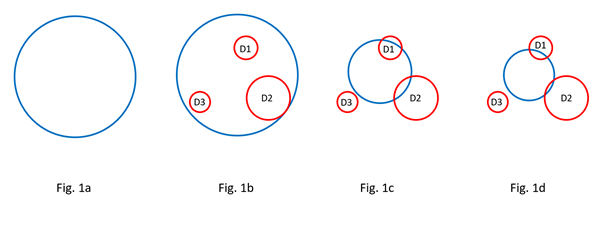

To help explain this concept, consider the following diagram which represents the invention defined by the claims as a circle with a given area. The area of the circle indicates the scope of protection.

So, a large circle indicates a large scope of protection that encompasses many different variations of the invention and a small circle indicates a relatively smaller scope of protection that covers fewer variations of the invention.

As shown in Fig. 1a, the claims of a patent application usually start off with a large scope of protection (represented by the blue circle). After all, we don’t know what the examiner will find in his/her patent search so there’s no sense in unnecessarily giving up some scope before we’ve had a chance to see the examiner’s objections (if any).

In Fig. 1b, we can see the examiner has found 3 citations D1, D2, and D3 that are considered to disclose an embodiment that has every feature of our claim. In other words, our claim lacks novelty over these 3 citations.

If the examiner is correct, we’ll have to amend our claim by including one or more additional features that are not disclosed by the 3 citations, thereby narrowing the scope of the claim and, hence, reducing the size of the circle (reducing the scope of protection).

The result of this amendment is depicted in Fig. 1c. As you can see, none of the 3 citations fall completely within the scope of our claim so we’ve now defined an invention that’s at least new.

However, there’s still some overlap between our claim and 2 of the citations, namely, D1 and D2. As indicated by the amount of overlap, D1 still shares many features in common with our newly defined claim.

In this situation, an examiner may accept that the invention defined by our claim is new but object that it lacks inventive step over D1 either on its own (because the distinguishing feature of our claim is obvious) or over D1 in combination with D2 (which may disclose the distinguishing feature missing from D1).

If an inventive step objection is raised by the examiner, we can either hold our ground and argue why the examiner is wrong, or we can introduce one or more further limitations to further distinguish our invention from the prior art.

In this example, we’ll introduce an additional feature to further distinguish our invention from the prior art, as shown in Fig. 1d. Here, you’ll see that the amount of overlap with D1 and D2 has reduced further, indicating that more features of our claim are missing from those citations.

In this situation, the examiner may accept that there are enough differences between our invention and the prior art that it would not be possible to arrive at our invention based on D1 alone or in combination with D2, and therefore conclude that our claim is inventive and, hence, patentable.

The goal of the applicant is to find a combination of features that provides adequate protection for the invention whilst distinguishing over the prior art in a new and inventive way. If this can be achieved, whether it involves no objections at all or several rounds of objections, the examiner will issue a notice indicating that a patent may be granted! Woohoo!

Grant Formalities

After acceptance, there’s usually a time restricted formality procedure to allow the application to proceed to grant. Often this will involve the filing of official form(s) and/or the payment of official fees to cover the patent office’s grant and publication procedures.

If all formalities are met within the applicable time limits, the patent office in question will issue a patent certificate to the proprietor and enter details of the patent into its official register.

The Granted Patent

So, you’ve toiled for years and finally obtained your patent. Now it’s time to use it!

Upon grant of the patent, the proprietor can enforce its rights against any unauthorised third parties that are working the invention as defined by the claims. This opens a range of commercial possibilities to the proprietor.

In the first instance, the patent proprietor can exclude all unauthorised third parties from working the invention in the territory in which the patent is in force. This, in itself, can give you a big competitive advantage.

But what else…

It might be that you’re not interested in making or selling your patent product or using your patented method. In this case, you could seek out potential interested parties that may be keen to make or sell your invention and offer a licence. Surely there’s nothing better than receiving royalties for doing nothing!

What if you’re not interested in making your product or receiving a royalty? In this case, you could consider selling your patent just as you might sell your car or apartment. If the patent protects something of commercial value, the patent itself will be valuable and may be sold to any interested party.

And it’s not all about making money! A patent can be useful for defensive purposes too.

What if one of your competitors has its own patent portfolio and tries to sue you for patent infringement? I’m sure you’ll agree your position will be significantly stronger if you own a patent that is infringed by your competitor! In this situation, your chances of reaching an amicable settlement may be greatly improved.

A company with a large patent portfolio is akin to a hedgehog with each of its spines representing a patent or patent family. A company with no patents is more like a turtle on its back with its soft underbelly exposed. You don’t need to think very hard to work out which of the two a hungry predator will go after!

Of course, not all patents are equal but if you can obtain a patent that covers a great product or process, it can be an invaluable commercial tool.

Now you may appreciate why Apple, Samsung, Google, Amazon etc. take obtaining patents so seriously!

Maintaining the Patent

One final thing to mention. After a patent is granted, it’s generally necessary to pay ‘renewal fees’ or ‘maintenance fees’ to keep the patent in force. These fees are usually payable annually and increase with age although some countries, notably the US, require that the fees are paid in tranches for multiple years.

Regardless of the payment requirements, you must be prepared to pay these fees during the lifetime of the patent, otherwise it will lapse, and you will no longer enjoy the benefit of protection.

It’s highly likely you’ll want to maintain commercially important patents so it’s vitally important you set up a renewal fee payment process to ensure your patents are not inadvertently lost.

The Takeaway

If you’ve made it this far, well done! Hopefully, you’ll now understand that filing a patent application and prosecuting it through to grant is a long and arduous process with many hurdles and potential pitfalls.

It’ll require a great deal of effort and perseverance but, if a patent can be obtained that will give you a competitive edge in your market, it can be well worth the effort.

If you’re interested in seeking patent protection for your idea and would like professional assistance from a qualified UK patent attorney, please contact us and we’d be happy to discuss your requirements and options.